Tell me about … Virtualization

Introduction

Virtualization solves a computing problem by adding a layer of indirection. The problem being: how to run multiple operating systems on a single computer; and the indirection: to slip a software shim between a guest operating system and the hosting platform, which continues to run its native operating system.

An example makes this clear. I work on an Apple computer which runs OS X, a flavour of BSD Unix. To develop portable code which will build and run on Linux and Windows as well as OS X, I use virtualization software. Using this software enables my Apple computer to run (for example) Windows XP and Linux Fedora Core 7 as guest operating systems alongside its native OS X. Effectively, I have three computers running on the same physical machine with no need for extra power supplies, keyboards, mice, monitors and so on.

The Parallels Desktop virtualization software I use doesn’t come free but it’s cheaper and more convenient than buying more hardware. VMware, perhaps the single biggest name in virtualization, does offer free entry-level products for doing a similar job on Windows and Linux platforms.

This article will not provide details on installing and configuring virtualization software, troubleshooting problems, and so on: the products have matured to the extent that these details are hardly needed, and any problems are quickly answered by online forums. We won’t attempt to explain how exactly virtualization works. Instead, we’ll talk more about what virtualization is, how we can use it, and why we should be interested it.

Virtualization in general

Before we go further I should explain this article uses the term “virtualization” in the specific way described in the introduction. More generally, in computing, virtualization refers to the abstraction in software of the platform on which a program runs. The Java Virtual Machine is a well known example, allowing software developers to build a single executable which should run on any machine. The JVM also isolates the application from the rest of the machine. These advantages, of portability and isolation, also apply to the full virtualization we’ll discuss in this article.

Creating a virtual machine

Setting up a virtual machine feels just like setting up a normal machine, except you don’t need new hardware. All you need is your host machine, the guest operating system media, and a suitable license to use it. With your host up and running, mount the install media, start up the virtualization software, click “Create new machine”, and follow the prompts. You’ll have to specify what resources to grant the machine (disk space, RAM, etc.) but very quickly you’ll be following the standard install procedure for your guest OS, selecting languages, packages and so on.

You don’t need actual physical media: you can create your virtual machine by booting it up from a DVD image on disk or over a network in much the same way.

Here’s one we made earlier

Actually, you may not require any install media. Your virtualization software is capable of booting up a pre-built virtual machine. VMware terms such machines virtual appliances. Running such an appliance is as easy as downloading it (which, at around 300Mb or less, requires far less bandwidth than a typical install image) and clicking on the downloaded file.

What you’ll typically be getting is a stripped-down Unix server, pre-built for a specific purpose, with stable, tested, compatible versions of whatever packages it requires for that purpose, and capable of operating within, say, 256Mb of RAM and as much hard disk as you’re prepared to allow it. You can run this Unix server on a Windows machine. You can reconfigure it. You can even transfer it to a different machine.

As an example, suppose you want evaluate Trac, an integrated version control and project management application. Trac may be open-source, popular and free, but I can personally vouch that on a Unix system it takes some setting up, and I can’t imagine getting it to work natively on a Windows server. Using virtualization, you simply download a virtual machine which has been loaded with the latest stable release of Trac. Boot up this machine using your host virtualisation software and run it on any supported operating system — Windows included. Do the same with Redmine, another web-based project management application, and you can compare it with Trac. Once you’ve completed your evaluation, delete the one you don’t like and keep going with the other. As a virtual machine, it’s easy to move it to a new host, if desired.

VMware provide instructions for creating appliances and host a library of such appliances on their website. Organisations like JumpBox make a business out of providing virtual machines which run on a number of different virtual platforms.

Running a virtual machine

Parallels Desktop creates shortcuts which I click on to power up the virtual machines. VMware on Windows does something similar. My perception is that these virtual machines boot as quickly as their physical counterparts would, but it could simply be that I’m using the host system to do something else while they start up in the background.

Exactly how the guest operating system integrates with the host varies. Some systems/configurations give you a window within a window; the guest user interface is displayed as a whole within a single window on the host, and you switch focus to this window to use it. More sophisticated systems integrate seamlessly, so you can tab between host and guest applications as if they were all running natively, and guest and host file browsers see both machines’ file systems transparently. The end-user experience is of the host and guest operating in parallel, as a single computer which can run software native to both systems.

In my experience, the first mode can be awkward to use. I much prefer the second: any friction context-switching between machines, and you find yourself preferring separate machines and a KVM, or using an X server to display X windows presented by a remote machine.

Peripheral Access

Which peripherals can the guest operating system access? Certainly, the guest wouldn’t be much use if it couldn’t make use of monitor, keyboard and mouse — although you may suffer translation and configuration wrinkles due to the different keyboard layout and mouse button conventions used by different operating systems.

Access to other peripherals and interfaces will depend on the virtualization software: check the product information. My guest Windows XP can use its host’s:

- network interfaces

- USB ports

- DVD drive

- speakers

- built-in camera

Actually, I didn’t realise it could use the camera, having never had cause to use the camera from within Windows, but a quick check shows it can. Access to networked printers also just works.

Opportunities

I’ve already mentioned some obvious uses for virtualization, and I’ll add some more which I’ve found useful in the past:

- you can develop for multiple platforms using a single machine

- you can download pre-built machines designed to run particular applications, saving you from package management headaches

- if you use a laptop, virtualization allows you to carry many machines around with you: a sales person could demonstrate Unix-based software on a Windows machine, for example

- you can script the creation of machines, and test e.g. clustered server configurations, without needing a rack filled with hardware

- you can test on multiple platforms

Even if your application itself is server-based and only runs on a single platform, virtualization allows you to test its web interface on multiple browsers. And even if your development is tied to a single operating system, virtualization allows you to keep old versions of that operating system alive on new hardware, and indeed to constrain the resources available to these old versions.

Hosting companies often use virtualization to create an indirection between user accounts and the hosting hardware farm. Users have root access to their own virtual machine yet are isolated from other root users on the same hardware (for example, rebooting a virtual machine doesn’t affect other machines on the same host); and their virtual machine can be transferred between physical hosts without them even realising.

It would even be possible to distribute software as a virtual appliance. Rather than requiring your users to install version X of Python, version Y of SQLite, version Z of the database bindings and so on, you might consider distributing an entire system which runs as a virtual machine.

Considerations

Running a virtual machine requires real resources. I deliberately chose Windows XP over Vista for this reason; XP has the smaller footprint and it’s all I personally need for developing software which ports to Windows.

As already mentioned, your guest operating system needs licensing. You need to pay to use Windows even if you’re running it on an Apple computer and have already paid for OS X. You’ll also need to go through the usual activation procedure.

You’ll need to tend to your virtual machines like any others on your local network. They need naming and backing up. User accounts must be created. Depending on what presence they have on your network, you may want to configure DHCP, or take anti-virus measures. You also need to consider upgrading them.

I have run into wrinkles and irritations with the hardware abstraction side of virtualization. For example, the Apple keyboard I use doesn’t map exactly to what I’d want when using Windows. It’s occasionally taken me some fiddling with X configuration files to get a Linux graphical interface displaying properly. Generally, though, someone else will have found and fixed the problem before you, and searching online forums turns up an answer.

In this article’s introduction we classed virtualization as yet another computing problem solved by indirection. Indirection has a price. What about the accumulated expense of everything passing through the software shim which abstracts the platform? Surely a guest operating system can’t be as fast as a native one on equivalent hardware? I have no hard figures to present here but personal experience suggests no perceptible difference: the only thing I have noticed is that my guest Windows XP seems to use only one of its host’s two CPUs.

Just for fun

We’ve seen it’s possible and sensible for a platform to host a guest operating system within its native operating system. How about trying something silly? Could our guest operating system itself use virtualization to become a host for a guest of its own?

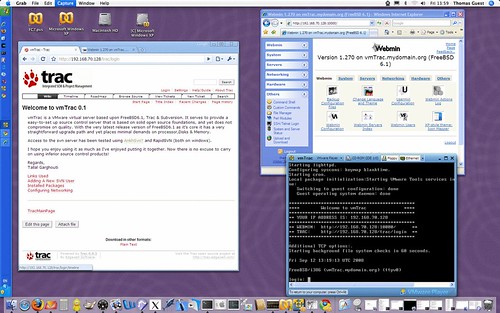

I gave it a go. Using Parallels Desktop on my OS X host, running Windows XP as a guest, I installed (the free) VMware Player virtualization software for Windows. So far, so good. Next I downloaded vmTrac, a 113Mb VMware appliance which packages Trac, Subversion, WebMin and Lighttpd on a FreeBSD core. I extracted the archive and opened the appliance using VMware Player.

The picture shows my desktop. I’ve used Google Chrome and Internet Explorer to access Trac and WebMin, which are running as web applications on FreeBSD, itself running as a Windows XP guest, and Windows XP is a guest on OS X.

Further reading

Although virtualization products are mature and modern hardware is ready to accommodate them, the options and possibilities still take some explaining. You’ll find plenty of good material on the VMware and Parallels websites. It’s also worth searching for other virtualization platforms. This is a growing market, there are lots of competitors and good deals to be had.

Testing on Multiple Platforms with VMware, by Anthony Williams provides a clear overview of the subject addressed in this article.

Thanks

This article was first published in CVu 20.5, an ACCU journal, and I would like to thank everyone at CVu for their help with it. In particular, I’d like to thank Gail Ollis, who edited CVu 20.5, and who suggested contributors should try and step back from the details of how to do something, and instead explain what exactly that something is and why it might be of interest.

This remit inspired several authors and CVu 20.5 turned out to be a great read. I particularly enjoyed Matthew Wilson’s article, “!(C ^ C++)”. Matthew Wilson is known as a C++ expert, but it came as no surprise to find he also knows his way around C. What did surprise me was to discover he prefers to use C in certain situations, and why.